Swedish documentary photographer Sebastian Sardi is innately curious. After reading an article about coal mining accidents in China in 2008, he decided that he wanted to see this first hand and to document the workers’ side of the story – shedding light on the lack of workers’ rights. From this beginning, his curiosity grew. Starting in China, he expanded to Russia, Kazakhstan, and eventually, India.

In India, he discovered coal mines that had grown around, and sometimes into, local villages, covering everything with a thick layer of fine dust. His photographs eventually turned into a book, titled Black Diamond, documenting the lives and conditions of those living alongside the coal. We sat down with Sebastian to learn what he finds important in documentary photography, and his workflow in capturing these coal miners and their environment.

What interests you most about documentary photography?

People, their lives, and their stories.

This series is focused on a very sensitive subject. When capturing difficult and sensitive subject matter, what do you take into account?

I approach people with respect and curiosity. Many times, the first interaction I have with a person is without a camera at hand. I talk to people as much as I can. In general, people are curious and show just as much interest in me as I do in them. It is common that they want to show me around or invite me places. I never take pictures of people who don’t want to be photographed.

It is very important to take into account where I am coming from and my background, as I have to rather quickly get to know and understand new people and new environments, and the mechanisms and social structures of the place. I have to express the right balance of curiosity and respect.

What do you try to capture in someone’s portrait?

Everything I can – feelings, emotions, expressions…as much as possible of that person. It may be a cliché that the eyes are the window to the soul, but I think eye contact is very important. It is how you first see a person, or a person sees you. It’s a meeting. It is the most basic human connection.

What equipment did you have with you? Why did you choose to use medium format?

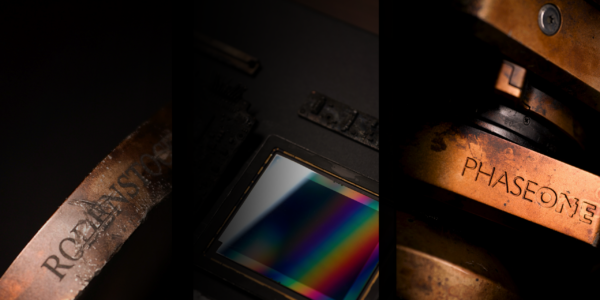

I started this project on analog medium format and a Yashica 124g as a continuation of my previous book about the circuses. It then evolved into digital medium format – Contax 645, Phase One IQ1 80MP, and then the XF and IQ1 100MP. I used the Schneider Kreuznach 80mm and 55mm lenses. No tripod.

I chose medium format because I like the waist level finder, as it does not block my face when I photograph and does not distance me from the subject. It goes back to eye contact. I also like the larger format and the image quality. Also, medium format is a slower form of photography. It allows me to take a bit more time when taking the picture.

What is the one thing you wish you knew when you started this project?

There is no specific one thing that I wish I knew before I started, but you get to know more about the world and yourself when working on topics like this. I guess that this curiosity for a broader world view and a better understanding of how I fit into the bigger picture is one of my driving forces and allows me mentally to take on such projects.

Can you explain your workflow?

I move around and walk a lot, so I need my gear as portable as possible. I use the waist level finder and small lenses. No tripod and no lighting – I shoot handheld with available light. I compose carefully and take as much time as possible to frame the subject. I may do some rough culling and basic adjustments while I am out, but I save most of that work for when I am back. I work really slowly and take my time on both shooting and in post.

I keep post-production and editing simple. With a background in analog photography, I tend to be a bit conservative sometimes, as I don’t want to alter too much. I would rather get it right in camera, which is the fundamental enjoyment of photography to me. Phase One cameras definitely help me in this regard. The image quality straight out of camera really allows me to minimize my post-processing and still get a fantastic resulting image. The tools in Capture One are more than enough for my type of work, so my images don’t generally require additional editing outside of Capture One.

Why do you print?

I like the final result not to be digital on a screen for people to scroll through in a never-ending flow. A well-made print on paper really comes out as a beautiful final piece of art. Like a painting. You can take your time looking at it and revisit it. How many times do you revisit your digital images? A print brings a certain permanence and yet always seems to carry a changing interest – you notice different details each time you view the print. Those characteristics are lost with digital.

If you could photograph anything, who or what would it be, and why?

Contemporary social and political issues is what I am and what I would photograph, because it affects people, us, me. It is our shared responsibility to be informed. It is important that we collectively broaden our world view, and photographs is how I can best contribute to this.

View more images from Black Diamond, and Sebastian’s other work, at www.sebastiansardi.com

Photographer Stories

Intimacy in focus: Louise’s lens on humanity with Phase One_Part1

Photographer Stories

Dimitri Newman: Vision is Just the Start

Photographer Stories

Ashes: The Rebirth of a Camera- Hexmalo

Photographer Stories

Chandler Williams: A Photographer’s Path

Photographer Stories

TABO- Gods of Light

Photographer Stories

Loreto Villarreal – An Evolving Vision

Photographer Stories

Tobias Meier – Storytelling Photography

Photographer Stories

Gregory Essayan – Curating Reality

Photographer Stories

Total Solar Eclipse – Matthew C. Ng

Photographer Stories

Roger Mastroianni – Frame Averaging

Photographer Stories

Matthew Plexman – Bringing portraits to life

Photographer Stories

Prakash Patel – A Visual Design Story

Photographer Stories

Karen Culp – Food Photography Ideas

Photographer Stories

T.M. Glass: Flower portraits

Photographer Stories

Preserving ancient Chinese buildings – Dong Village