“Architectural photography is much more than documentation. It’s the challenge to translate an architect’s design vision from 3D into a 2D media – translation that can create both a meaningful and a graphically powerful image that begins to reveal the design story.”

How do you approach an assignment?

Ideally, I like to meet on site with the designer and walk the project before the shoot. Usually during this process, the key design concepts or ideas are revealed, and I try to weave these ideas/concepts into the visual story for the project photography.

How have your artistic challenges changed with photographic advances?

Early in my career, I was shooting with 4×5 F-Metric Arca-Swiss view cameras and film. Later, when early digital backs came to market (Phase One H20) I had a sliding back prototype Cambo camera, viewing through ground glass where the image appeared upside down and reversed just like my analog 4×5 camera. Back then, controlling technical parameters like contrast and color control to shoot on transparency film was quite challenging, as it had to be done in-camera and on-site. Translating a black and white polaroid proof into color film also meant dealing with different color temperatures of daylight, fluorescent and incandescent lighting for interior shots, details that today can be handled more easily by current digital sensors and post-production software techniques. The technological advances of digital sensors, proprietary features of camera systems, advances in lighting gear, and maturation of post-production software definitely broaden the visual vocabulary of the photographer. It’s a great time to be a photographer because the limitations of the medium, from both capturing the image to producing the image, have become more integrated.

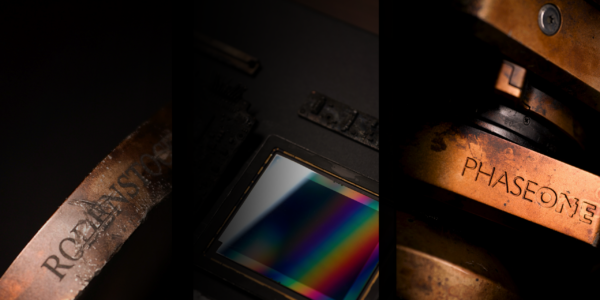

What role does Phase One equipment play in your work?

I became a Phase One customer in 2006 because their image capture was – and still is today – a superior solution. Being an architectural photographer, your vision can be limited by the tools you carry, and I’ve always wanted to have lenses with the largest image circles and a camera system with the largest sensor size that can handle those movements. I like to have a broad enough toolset (both wide and long lenses) to be able translate a client’s design solution effectively. The IQ4 150 camera digital back is a spectacular capture device. I like its low-light capability and features, such as dual exposure and frame averaging. While shooting the Partigiana sculpture in Venice, I was able to use the frame averaging feature to dial in the appropriate amount of motion blur of the water without needing to change various strengths of neutral density filters. I could bracket the amount of motion blur quickly and in between the busy water taxi traffic.

What does it mean to you and your work that the XT was the first technical view camera where the lens talks directly to the back electronically? Has it changed the way you worked?

Prior to the XT camera, I used both the Cambo and Arca Swiss technical cameras. I had gotten used to recording both the rise/fall and horizontal shift movements for every shot. We would then insert those movements into Photoshop via an Alpa plug-in to correct any distortion from using the Rodenstock retrofocus lenses. Once the XT camera system with the X-shutter lenses was introduced, the lens displacement movements were automatically recorded in the metadata of the raw files. All of this was integrated into Capture One (raw file processor) and you could simply use a slider to adjust the amount of distortion correction.

I love the XT camera’s compact size, ergonomics, and capture trigger on the body. In my personal work, I am often in locations where I am not able to use a tripod without prior permission. So, it is quite handy to be able to shoot handheld and have files that are the highest resolution. This small form factor works very well for both interior and exterior photography where the lens displacements are less than 12mm. I also have a second Cambo WRS body for when I need more than 12mm of movement. In this configuration, the workflow interface and the feature sets remain the same with the IQ4 and the XT shutter lenses by simply connecting the XT lens to the IQ4 via cable. These innovations allow the tech camera to be used with the same speed and simplicity as a 35mm or cropped sensor DSLR.

In fact, my current workflow using the XT body is much simpler than using a 35mm or cropped medium format DSLR style camera. It is a simple touch screen interface for all necessary camera functions as opposed to dials and special function buttons to navigate through complex menu systems.

In addition to proprietary Phase One features, I have the added compositional benefit of capturing with a larger sensor. I can better control the natural optical distortion of objects in the scene by shooting wider and cropping. This strategy of shooting wider and cropping is also very handy when you need a tight detail view and need to hold a deeper depth of field. These benefits in higher megapixel capturing devices are often overlooked.

What about lenses?

My Rodenstock 23,32,40 tilt, and 50mm have X-Shutters that work with both the XT body and the Cambo WRS 5000. The X-shutter allows me to blur people or cars using a longer exposure without the geometric distortion of the electronic shutter. Additionally, it allows me to sync strobes with higher shutter speeds. I also have the 19mm (Cambo WRE-2019) that works on the XT in electronic shutter mode for ultra-wide angle shots with 4-5mm of movement. I have both Rodenstock and Schneider lenses for longer focal lengths between 60mm -210mm on an Arca-Swiss M2 view camera to utilize the larger image circles.

You’re working on a project that you call a “labor of love.” Please tell us about The Architecture in Conversion which you and Frederica Goffi are writing. Will you use Phase One equipment for that project?

You could say the project is a labor of love of Architecture. I reconnected with Federica, a colleague and scholar at an Architecture Symposium, and she mentioned she was researching the work of Carlo Scarpa. She extended an invitation to meet in Italy, and not having seen any of Scarpa’s work in person, I took her up on it, knowing that her expertise would give me a different perspective of Carlo Scarpa’s work. The trip in 2017 went well and I was invited again the next year. Following a joint exhibition and lecture at Carleton University in 2018, Federica proposed a book project to a publisher, and it was accepted. While the timeline changed significantly due to the Covid shutdown, work on the project continues. In the future, we hope to have a joint exhibition with publication of the book.

Carlo Scarpa’s architectural work is highly detailed, the materials he used had various luminous reflective properties. His work was ideal for subtle toned high-resolution photography. Initially I was working with the IQ3 100 and then I upgraded to the IQ4/XT platform when it came to market because I knew it would be an asset for this project as well as my commercial work.

Below is a synopsis of this book project along with a video link to the Carleton Exhibit as a reference to the work of Carlo Scarpa.

Architecture in Conversion: Time, Weather, Tempo in the Work of Carlo Scarpa – Lund Humphrey 2025

Federica Goffi, Author

Prakash Patel, Protography

The book investigates the notion of conversion in architecture through the lenses of Carlo Scarpa’s work. The textual and photographic research is based on the interpretation of archival materials through historical research and interviews with those who assisted Scarpa in different projects. Collaborators were met on site to allow for memories to resurface and stories to unravel in such a way that unique details about the design process could emerge, like the fact that Scarpa would visit the site at night with a construction light to observe details or how he would lay on the floor at Castelvecchio to look at the ceilings details from this point of view. The interpretation thus places itself in between the historical datum and an imaginative speculation through both textual and photographic means to transform the ‘seeing as’ into a ‘seeing in.’

Learn more about Prakash Patel here

Check out Carleton Exhibition here

Photographer Stories

Intimacy in focus: Louise’s lens on humanity with Phase One_Part1

Photographer Stories

Dimitri Newman: Vision is Just the Start

Photographer Stories

Ashes: The Rebirth of a Camera- Hexmalo

Photographer Stories

Chandler Williams: A Photographer’s Path

Photographer Stories

TABO- Gods of Light

Photographer Stories

Loreto Villarreal – An Evolving Vision

Photographer Stories

Tobias Meier – Storytelling Photography

Photographer Stories

Gregory Essayan – Curating Reality

Photographer Stories

Total Solar Eclipse – Matthew C. Ng

Photographer Stories

Roger Mastroianni – Frame Averaging

Photographer Stories

Matthew Plexman – Bringing portraits to life

Photographer Stories

Karen Culp – Food Photography Ideas

Photographer Stories

T.M. Glass: Flower portraits

Photographer Stories

Preserving ancient Chinese buildings – Dong Village

Photographer Stories

Jeff Puckett – The Art of Photogravure