Harold Ross is an American fine art photographer who has been mastering the art of light painting for the past 30 years. His work has been exhibited, published and collected all over the world. Today, he teaches his unique technique of sculpting with light through his blog and regular workshops.

My love story with photography started, as it does with many photographers, while standing next to my father in the darkroom, when I was very young. I’ll always remember those moments of watching the images come up in the developer tray. This seems rather quaint in today’s age of electronic devices, but back then it was truly magical. I remember wanting to recreate that magic for myself. At sixteen I bought my first camera, a GAF Instamatic, which I still own. I remember having so much fun photographing family and friends, and then developing the film and making prints in the darkroom. Both my father and my uncle were amateur photographers, and there was no shortage of good advice and technical help. It was during this time that I decided that I would aspire to become a professional photographer. I then attended art school at Maryland Institute, College of Art, which was a life-changing experience.

Later, I specialized in still life photography. What I love about it is that it embodies at once the contrast between ultimate control and the unknown. What I mean by that is that, in the studio, you start with nothing and have to build from it. The content and the composition are completely up to and dependent on the photographer, which can be a little daunting. On the other hand, I love the complete control over lighting that the studio offers, and light painting gives me further control over depth and dimension.

I don’t only shoot objects. I also love to photograph the environments that people work in. Much like the tools and machinery they use, artisans need a workspace that is properly designed for their specific purpose, and often these spaces are “decorated” by their occupant over the years, which I find to be very interesting. I enjoy the challenge of light painting these larger and more complex scenes, and I hope to evoke the same feelings I myself have when visiting these spaces.

In the eye of the beholder

In addition to photographing typically beautiful subjects, I’m probably more drawn to shooting subjects that one might not consider inherently beautiful. In some cases, these objects are ignored and might even be discarded. I also have an appreciation for designs of the past, and for how objects were designed for function and efficiency.

I have a great respect for people that work with their hands, and especially the tools and machinery that they use. My grandfather, a blacksmith trained in his home country of Switzerland, taught me to have a reverence for hand-crafted objects. My goal (and I’m sure that a lot of photographers share this goal) is to give the viewer the same feeling that I have when I really look at these things. My process of light painting helps me do that.

In fact, my grandfather also taught me how to work with metal. I do some creative welding and a small amount of blacksmithing, all sculptural in nature. I’ve also always felt a connection between photography and sculpture, which I studied a bit in art school. In sculpture, as in photography, achieving depth and volume is one of the main challenges. Having a feel for form and depth, and thinking sculpturally have definitely informed my photographic approach.

Sculpting with light

My method of light painting, which I call Sculpting with Light, is the only photography method I use. I started using light painting in my commercial work by using small flashlights in order to get light into difficult areas. I’ll never forget the first time I “peeled” a Polaroid (I always shot 4×5 and 8×10 sheet film) and saw that the light-painted area of the image was much more beautiful than the other areas! I immediately thought: “Why not just light paint everything”? After that, I embraced light painting as my only method of lighting. There was a gifted photographer named Aaron Jones, an excellent light painter. Aaron developed a system to make light painting easier and more effective, and after purchasing it, my light painting was much more controllable and repeatable. Aaron and I are still in touch occasionally!

Now, with the process that I’ve developed for the digital workflow (which, by the way, stems directly from film techniques), light painting is even more controllable, and the results are more beautiful than what I could ever achieve on film.

Since my images are created with multiple captures, they don’t really exist fully until the post-production stage. This feels a bit like in the old days when we didn’t fully see an image until the film was developed. Because of this, and due to the heightened transformative nature of light painting, the composition may not initially be as exciting as one would hope, and this can cause issues with perception at the time of the shoot. For this reason, I always use light painting in the composition stage as well to get a sense of the potential of an image.

"When looked at from a certain viewpoint or camera angle, and with lighting that brings out the otherwise hidden aspects of an object, we can make the seemingly mundane into something truly extraordinary."

I now teach light painting as well. I developed my own method of using multiple captures and powerful masking techniques which relate more to painting and drawing, and is therefore a technique which is not taught by any other photographers. I’ve also codified the principles of light into easily understandable concepts that help my students get to a high level of ability in a very short time. If you want to learn more about my teaching material, you can take a look through my blog for tutorials and guidance.

Tools of the trade

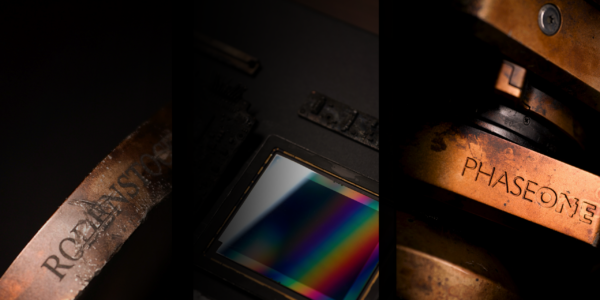

I shoot medium format because my work is in large part about depth, dimension and detail. Medium format provides the resolution I require and a smoothness to the images that helps my work get across the feeling I’m after. Phase One was the first camera to allow a longer exposure for light painting, and since my first back (an H16!), Phase One has been at the forefront of technology and advances in image capture. The quality of the files that they provide is without equal. Personally, when it comes to equipment, I don’t look for “bells and whistles”, but rather for dependable, robust equipment that is rock solid. Phase One dependably provides that.

I print out of Photoshop, and I have my own methods involving resolution and sharpening. I first pre-sharpen an image in Capture One using a type of sharpening that involves a very small radius and a high amount, with very little threshold. After I am finished with post-production, I create a semi-flattened “Print Master” file at native size, which I sharpen in Photoshop using a simplified smart sharpen routine. I then re-size this file to the desired print size without re-sampling, and I never have to sharpen again (except when re-sampling for a Jpeg, for example). The images print beautifully even when the resolution “floats” as the size changes. This process is not in accordance with the concept of “sharpening for output”, but it works well for me, and I consider myself to be quite critical when making prints.

I print in limited editions, with a maximum of 20 prints, no matter the size. I print on cotton rag paper, usually matte, and I prefer a heavier paper of 320 or 365 GSM. I print using a Canon Pro printer, having formerly printed with Epson. I very much prefer the Canon, as clogged nozzles, at least for me, are now a thing of the past. Canon printers automatically agitate the ink, which helps, and I like the fact that the print heads are user-replaceable (in 5 minutes!). I also very much like the Canon software, which allows a “ring-a-round” method that helps me arrive at a great print very quickly.

I also sell prints on aluminum (dye-sublimation), and I’m a big fan of Blazing Editions. Their quality is without equal, and their customer service is top notch.

Throughout my career, I’ve worked with different galleries to publish and sell my work. This has undeniably helped my development as a photographer, and informed my approach to sharing and selling my work. If you’re at a point in your career when you’re considering working with galleries and selling your work, I hope this guide I put together will prove useful.

Being a photographer

The hardest part about being a photographer is fighting the fear of failure. I think that all artists wrestle with this, some more than others. It’s difficult to ignore the little voice that says: “What if this doesn’t work? Is this worth the time? Will I like this when I am finished?” Although it’s gotten easier, this is one of the biggest hurdles I’ve been struggling with.

One of the best parts of being a photographer is the way it makes me see the world. I am so glad that when I look at a scene, an object or a painting, I see it through the eyes of someone who thinks about color, contrast, brightness, and the nuances of how light falls on a subject. I feel that this ability enriches life tremendously.

If I had to compress my photography into one single message I’m trying to communicate, it would be this: There is beauty everywhere. We can walk into the backyard and find a beautiful leaf or an amazing feather, take a longer look at things that others pay no attention to. When looked at from a certain viewpoint or camera angle, and with lighting that brings out the otherwise hidden aspects of an object, we can make the seemingly mundane into something truly extraordinary.

Photographer Stories

Intimacy in focus: Louise’s lens on humanity with Phase One_Part1

Photographer Stories

Dimitri Newman: Vision is Just the Start

Photographer Stories

Ashes: The Rebirth of a Camera- Hexmalo

Photographer Stories

Chandler Williams: A Photographer’s Path

Photographer Stories

TABO- Gods of Light

Photographer Stories

Loreto Villarreal – An Evolving Vision

Photographer Stories

Tobias Meier – Storytelling Photography

Photographer Stories

Gregory Essayan – Curating Reality

Photographer Stories

Total Solar Eclipse – Matthew C. Ng

Photographer Stories

Roger Mastroianni – Frame Averaging

Photographer Stories

Matthew Plexman – Bringing portraits to life

Photographer Stories

Prakash Patel – A Visual Design Story

Photographer Stories

Karen Culp – Food Photography Ideas

Photographer Stories

T.M. Glass: Flower portraits

Photographer Stories

Preserving ancient Chinese buildings – Dong Village