Harold Ross is an American fine art photographer who has been mastering the art of light painting for the past 30 years. His work has been exhibited, published and collected all over the world. Today, he teaches his unique technique of sculpting with light through his blog and regular workshops.

If you’re at a point in your career where you’re considering working with galleries to sell your work, here are a few questions I think you need to ask yourself beforehand:

Do I want to work with limited editions?

Whether you want to work with limited editions is a big and very important decision. Once decided, it’s difficult to change, so give this a lot of thought. Basically, if you work with higher quality galleries, limited editions are desired, as collectors of your work will want to have confidence that there will be a limited supply of your prints. This means that, all things being equal, your limited edition prints will have more inherent value than if you offered open editions (no limit to the number of prints).

How many prints should be in my limited edition?

There are photographers that sell only one print per image, and others who may offer 100 or more! Some photographers offer limited editions within certain sizes, i.e., 15 prints at 16”, 10 prints at 24”, 5 prints at 40”, etc. Obviously, the lower the number, the higher potential price (again, all other things being equal). I, for one, offer only 20 prints per edition, no matter the size. Once an edition sells out, no more prints are made of that image.

Some photographers have a sliding scale for pricing: as the edition sells, pricing goes up, and so the last print costs more than the first. This works as an incentive for collectors to buy early in the edition, as their investment increases in value as the edition sells.

Whatever you choose to do, you must never lower the price of prints in an edition. This will undermine the value of previously purchased prints and will do a disfavor to your current collectors. Therefore, pricing on limited editions can only increase, never decrease. This also means that, whether you sell directly or through a gallerist, your pricing should be the same.

What about open editions?

Given the high demands of working with limited editions, many photographers prefer to sell prints themselves, or through galleries that don’t require limited editions. The advantages are many: pricing is more flexible and variable, record keeping is easier, and a very popular image can sell for years and years, with the profit on it getting higher. In general, prices for open editions are lower, but you might sell many more prints of a given image. All things considered, you need to choose the best scenario for yourself.

Am I ready for a lot of record keeping?

Obviously, it is very important that you keep track of all sales, including pricing and edition numbers. This requires quite a bit of work, although there are some software programs to help. When working with limited prints, it is also a good idea to provide the buyer with a signed “Certificate of Authenticity”, which provides provenance for the print.

Is working with a gallery worth it?

I certainly think so! A good gallerist adds their own set of qualities to selling your work. They bring their valuable experience and hard work to the table, while also being a great advocate for your work. They know how to talk to clients about photography, putting your work into context with other work, as well as with the history of photography, thus providing the potential buyer with the information they need to appreciate your work. A professional gallerist is worth their weight in gold!

How do I meet gallery people, editors and curators?

My best advice is to participate in portfolio reviews. Photo Lucida (Portland), ACP (Atlanta), PhotoNOLA (New Orleans) are three of the most well-known reviews in the US. They provide the opportunity for face-to-face meetings with editors, gallerists and curators, and is the best way to get your work looked at. Attending these reviews offered me tremendous opportunities. The Lenscratch blog has listings of all portfolio reviews.

When you are submitting your work for review, I would suggest showing work which has a distinct visual thread. To an experienced curator, a portfolio that is “all over the place” in subject matter or process is a sign that the photographer has not yet found their vision. Conversely, having a body of work that works together, whether it be content and/or process, is much more attractive. It shows that the photographer has a strong identity and is capable of producing work at a consistent level.

Photographer Stories

Intimacy in focus: Louise’s lens on humanity with Phase One_Part1

Photographer Stories

Dimitri Newman: Vision is Just the Start

Photographer Stories

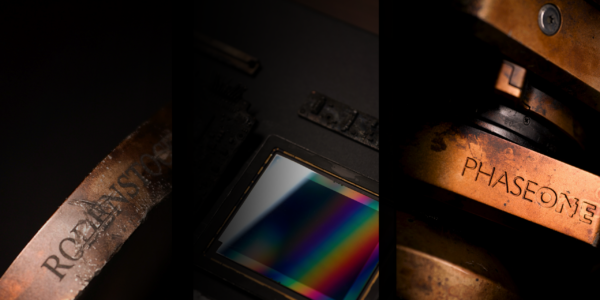

Ashes: The Rebirth of a Camera- Hexmalo

Photographer Stories

Chandler Williams: A Photographer’s Path

Photographer Stories

TABO- Gods of Light

Photographer Stories

Loreto Villarreal – An Evolving Vision

Photographer Stories

Tobias Meier – Storytelling Photography

Photographer Stories

Gregory Essayan – Curating Reality

Photographer Stories

Total Solar Eclipse – Matthew C. Ng

Photographer Stories

Roger Mastroianni – Frame Averaging

Photographer Stories

Matthew Plexman – Bringing portraits to life

Photographer Stories

Prakash Patel – A Visual Design Story

Photographer Stories

Karen Culp – Food Photography Ideas

Photographer Stories

T.M. Glass: Flower portraits

Photographer Stories

Preserving ancient Chinese buildings – Dong Village