T.M. Glass is a digital artist based in Toronto, whose practice explores the historical, technological, and aesthetic conditions of photography, stretching it beyond its traditional definition. Once a student of sculpture and fine art at the Ontario College of Art, Glass returned to art after building a successful career as a writer and producer in film and television. Today, the artist’s vision is channeled into hyper-realistic still life photography combined with digital painting.

If I had to trace back the catalyst for my photographic beginnings to a precise point in time, I would say it all started when I saw a painting by Claude Monet at the Art Gallery of Ontario in the late 1990s. It was a simple still life painting, lilac flowers in a jug, but the composition, light, shades and colors were so beautiful they captured my attention and my heart. I stayed looking at it for the longest time, and years later I can still remember how strongly that 100-year-old painting reached out to me. It was Monet’s artwork that inspired me to create a still life picture of my own. Mine looked very different because I was using different artist tools, a photo camera and digital tools, but Monet’s spirit remains behind all my body of work.

Going back in art history

As a student in sculpture and fine art I discovered that the link between sculpture and photography is the use of light and shade to define the imagery.

Throughout art history, the availability of tools has had a great impact on the kind of art that could be produced, whether it was a lump of chalk in the hands of ancient cave painters, or oil paint on canvas. A pivotal moment was the 1960s introduction of a new artist tool: acrylic paint. Acrylic could create a hard line (if you had a roll of masking tape) and flat surfaces, things oil paint could not do. From that time contemporary art embraced flat imagery and hard edges, abandoning the illusion of depth which was something oil paint did better than acrylic. The exception was contemporary photography which continued to include the depiction of depth.

The introduction of digital art tools – cameras, software and printers – struck me as a moment just as important as the introduction of acrylic paint, and motivated me to start experimenting with them. Early printers had ink that changed colors after a week, but soon archival inks and papers arrived, along with printers that could deliver high resolution images.

My first digital experiments included attempts to create still life pictures inspired by Monet. That’s when I discovered that digital software had all the tools needed to create paintings that included the illusion of depth. After 60 years of flatness, I decided that it was time for digital painting to bring a return to the illusion of depth. I then went forward in challenging other 60-year-old conventions of contemporary art including minimalism, simplicity, abstraction and the avoidance of beauty.

In full bloom

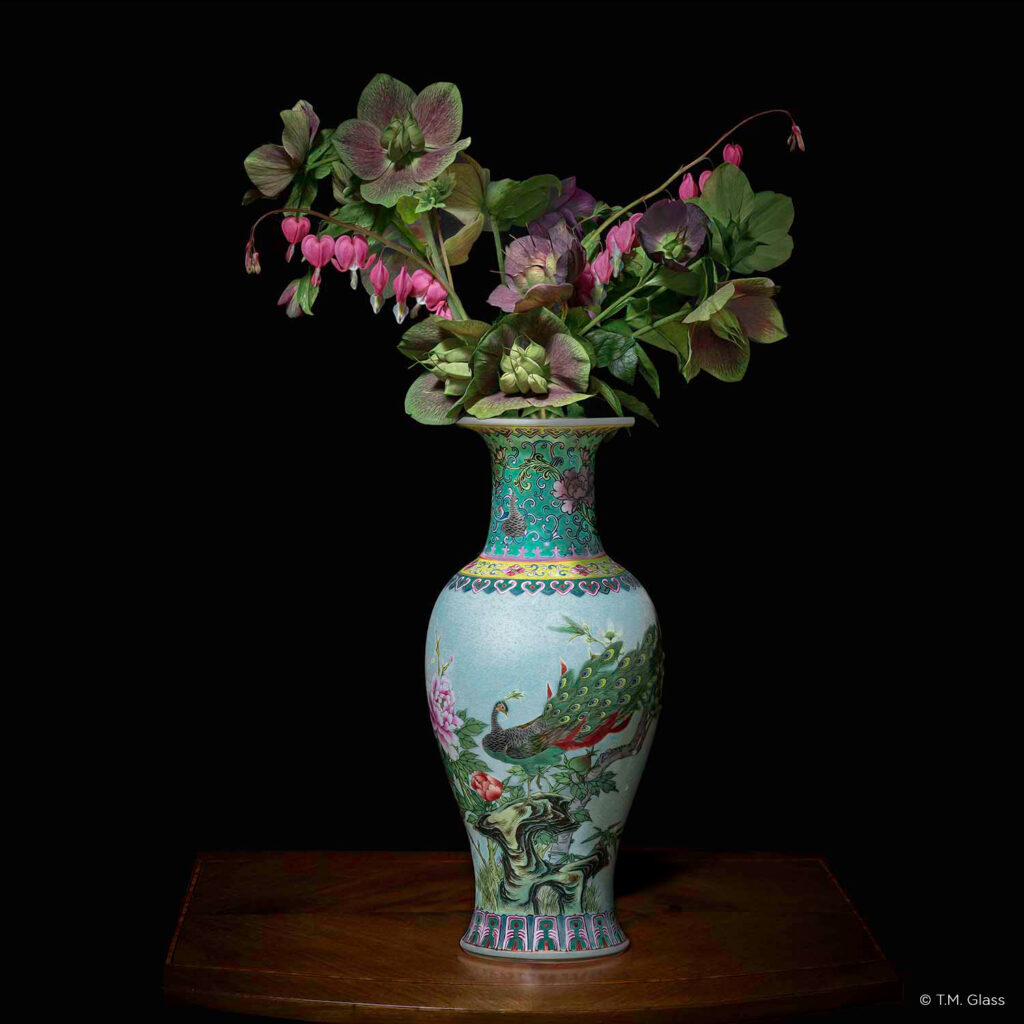

I started taking pictures of flowers as I was documenting the creation of our house garden. Those documentary garden shots led to still life becoming the central focus of my artist practice.

But my fascination with flowers as subjects has even deeper roots. The central concept of the 19th century Arts and Crafts Movement, a quest for beauty quickened by a sense of approaching death, is perfectly epitomized in the flower, one of the most beautiful things on earth that, once cut, soon dies. The language of flowers is always present and speaks to us on the most important moments of our lives, at weddings, funerals, births, sick rooms, Valentine’s and Mother’s Day, in hotel lobbies, at political conventions and so on. Flowers can express so many varied emotions, such as love, loss, hope, congratulations or apologies.

I began with flowers cut from my garden in vases from my home collection. When I ran out of interesting vases, I started working with museum curators who allowed me to photograph vessels from the museum collections. However, I was not allowed to touch the vases or put flowers in them. That meant I had to do two photoshoots: one at the museum and the other in my garden. I then used digital paint to merge the photographs, and worked with the digital paint to create the final painting.

Some of the flowers in more recent pictures are from gardens that are not mine. In England I photographed flowers from a garden the Queen Mother created. In India I worked with a florist who arranged flowers in vases I rented from an antique dealer. In Quebec I worked with the gardeners at the historic Jardins de Metis and their flowers were arranged in vases from the Jardin’s museum.

I believe my photography communicates on different levels. The messages I build into my images are first and foremost messages to myself, secret and private like a poem or a song. People who then see the pictures in an exhibition or at a gallery take away their own private reactions, thoughts and feelings, the way they do when they attend a music concert or see a movie.

Technology in the service of art

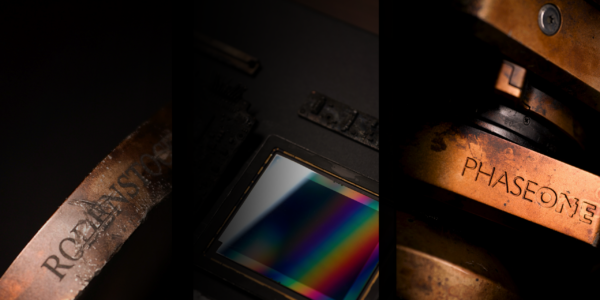

In the beginning, I was using small point-and-shoot digital cameras, but as better and better digital cameras and software were developed I got hooked. I always wanted to work with the latest and best. Nowadays, my limited edition pictures are printed in several sizes, with the largest size being 58”x58”. To create such large pictures, the camera I use must deliver high resolution. That is why Phase One is the best camera for the work I do.

I fully embrace technology and use digital tools in my work to mix colors, collage bits and pieces of images, hand paint with digital paint, add and subtract. In other words, I do with digital hardware and software whatever I might do if I were using physical paint. Unlike a traditional painter, I create my art on a computer with input from a digital camera and a digital painting tablet and stylus. The created digital painting is then exported digitally from the computer to a digital printer. I do all the printing myself in my studio, with a six-foot Epson and on handmade archival rag paper imported from Italy.

But I’m not stopping here. In recent years I’ve starting experimenting with other emerging technologies that can benefit art, such as 3D printing flowers or using a Midi Sprout to translate plants’ natural electromagnetic vibrations into sound and thus make flowers “speak”.

The Art On Paper Exhibition

Between 5-8 March you can view six large format T.M. Glass pictures (58”x58” and 52”x52”) at the Art On Paper fair at Manhattan’s Pier 36. At the fair will be present 100 galleries featuring top modern and contemporary paper-based art, with cultural partners such as MoMa, Brooklyn Museum, Bronx Museum, Whitney Contemporaries, Sotheby’s Preferred.

As part of Art On Paper, Henderson Lee Gallery is exhibiting a T.M. Glass solo exhibition with a selection from T. M. Glass’ 30-picture collection of limited editions. Uniquely singular in style, these T.M. Glass large format digital paintings bring an entirely original twist to the historic still life flower painting, joyously breaking contemporary art conventions and combining the latest in digital technology with the visceral impact of traditional painting.

Photographer Stories

Intimacy in focus: Louise’s lens on humanity with Phase One_Part1

Photographer Stories

Dimitri Newman: Vision is Just the Start

Photographer Stories

Ashes: The Rebirth of a Camera- Hexmalo

Photographer Stories

Chandler Williams: A Photographer’s Path

Photographer Stories

TABO- Gods of Light

Photographer Stories

Loreto Villarreal – An Evolving Vision

Photographer Stories

Tobias Meier – Storytelling Photography

Photographer Stories

Gregory Essayan – Curating Reality

Photographer Stories

Total Solar Eclipse – Matthew C. Ng

Photographer Stories

Roger Mastroianni – Frame Averaging

Photographer Stories

Matthew Plexman – Bringing portraits to life

Photographer Stories

Prakash Patel – A Visual Design Story

Photographer Stories

Karen Culp – Food Photography Ideas

Photographer Stories

T.M. Glass: Flower portraits

Photographer Stories

Preserving ancient Chinese buildings – Dong Village